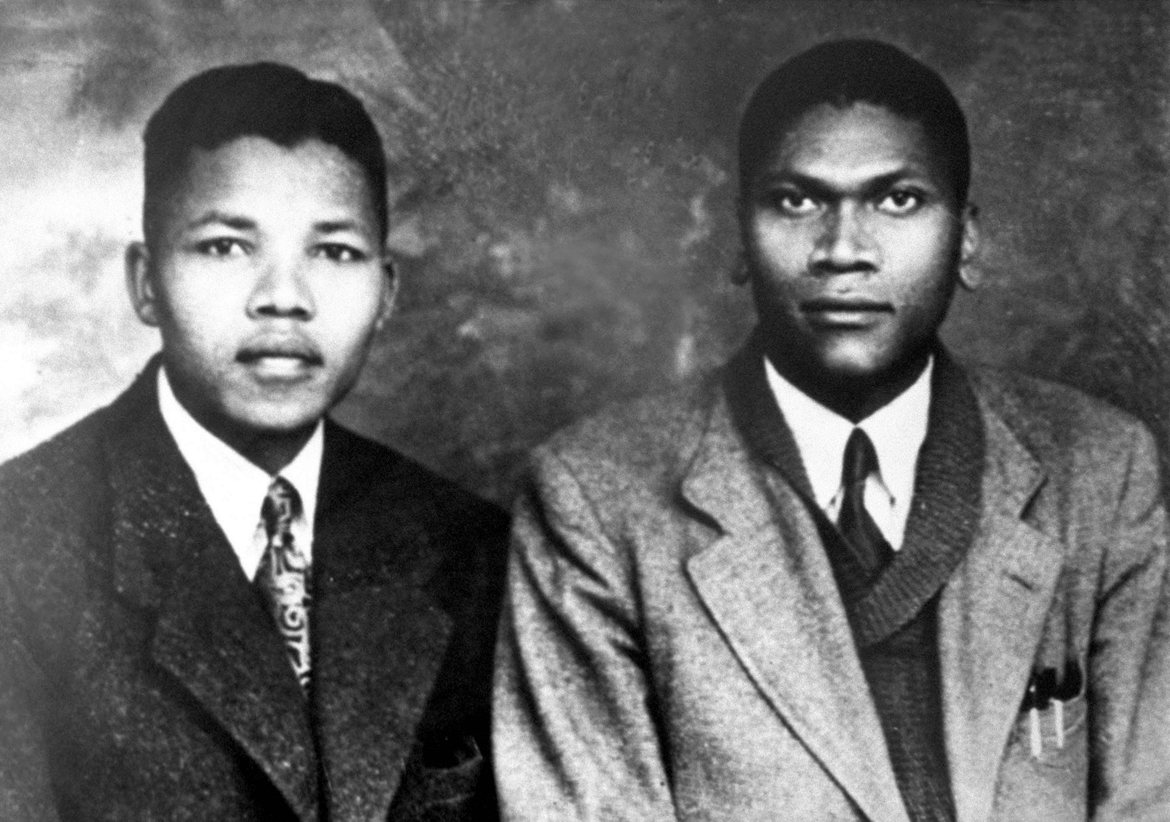

Mandela and his friend Bikitsha, circa 1941, Courtesy Professor Charles van Onselen

“If I must die, let me declare for all to know that I will meet my fate like a man.” These are the words on the handwritten note that Nelson Mandela intended to read out in the event that he was given the death sentence at the conclusion of the Rivonia Trial in June 1964. Half a century later the globally beloved Mandela, fondly known as Madiba, could look back on his time on Earth and know that he met his fate “like a Man”.

In his lifetime Mandela developed the qualities of a man amongst men and a true leader; qualities of strength, courage, mercy, kindness, perseverance and self-reflection, and pursued his lifelong quest for all persons to be treated, as he said “in conformity with civilised standards”; standards that respect human dignity irrespective of colour, creed or culture.

This was his life motto, a motto he proclaimed to the world at the conclusion of the Rivonia Trial Statement and a motto that he has repeated throughout his life:

“I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against White domination, and I have fought against Black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an idea which I hope to live for and to achieve. But, if needs be, it is an idea for which I am prepared to die.”

Standing in the dock on that pivotal day in 1964, armed with his ‘in the event of death’ note, penned on a modest piece of exercise book paper, Mandela had to face the reality of his life abruptly ending at the age of 46: an age when most men and women are reaching that powerful nexus of vigour and maturity; an age when Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was ready to assume a powerful, public leadership role.

Unexpected facets of himself

In his autobiography Long Walk to Freedom and in Conversations With Myself (a selection of diary entries, excerpts from letters, private ‘to do’ lists and other textual snippets), Mandela reveals unexpected facets of himself, often at odds with the public image of the joyous, victorious political icon and liberation hero. We encounter a man acutely aware of his own vulnerability; at times at war with himself and with his passions; a man whose loyalties are divided between his family and “the family of the people”.

In Conversations with Myself (pg. 172), it reads: “He has known pain and devastation – countless indignities, severe and irrecoverable losses (including the loss of children); dramatic separations and invisible wounds; grief, helplessness and mourning, the kinds of experiences that “eat too deeply into one’s being, into one’s soul”.

He turned his wounds into a private secret

.jpg) On pg. 32 of Long Walk to Freedom it says: “Throughout his active life, Mandela consciously drew a veil over his wounds and misfortunes. He turned his pain into a private secret he was loath to exhibit in public. While he offered his outer self to the political sphere of men, he shared his inner self with privileged women friends. “… With women I found I could let my hair down and confess to weaknesses and fears I would never reveal to another man”.

On pg. 32 of Long Walk to Freedom it says: “Throughout his active life, Mandela consciously drew a veil over his wounds and misfortunes. He turned his pain into a private secret he was loath to exhibit in public. While he offered his outer self to the political sphere of men, he shared his inner self with privileged women friends. “… With women I found I could let my hair down and confess to weaknesses and fears I would never reveal to another man”.

“The truth”, he wrote to his daughter Zinzi Mandela in 1970, is that “my appearance had nothing to do whatsoever with the state of my feelings” (Conversations With Myself, pg. 189)”. The ethos of the struggle, he argued, required of the freedom fighter that he or she suppress many of “the personal feelings that make one feel like a separate individual rather than part of a mass movement” (Long Walk to Freedom, pg. 215).

Yet when it came to death or departure he, like all of us, battled with his personal feelings of sorrow and loss:

Of his son Thembi’s death he said: “I do not have words to express the sorrow, or the loss I felt. It left a hole in my heart that can never be filled.” Of his close friend and compatriot Walter Sisulu’s death he said it left him “almost prostrate with grief”.

Each death or ending or leaving not only meant walking toward some other place, some other world; it also implied mourning the world and the past left behind, usually in silence; silence as a response to the pain of separation, which he called “the silence of the heart”.

The need to develop a private and public world

A man of deep, dramatic emotion, Madiba recognised the need to develop a private and a public world from a young age.

A man of deep, dramatic emotion, Madiba recognised the need to develop a private and a public world from a young age.

The split between Mandela’s inner and outer self and its relationship to manhood and later to leadership is nowhere as manifest as in the scene of circumcision and seclusion, of which Mandela offers a vivid and arresting tableau in Long Walk to Freedom: “I looked directly into his [the ingcibi, the old man performing the ritual] eyes”, Mandela writes. “Without a word, he took my foreskin, pulled it forward, and then, in a single motion, brought down his assegai. I felt as if fire was shooting through my veins; the pain was so intense that I buried my chin in my chest. Many seconds seemed to pass before I remembered to cry, and then I recovered and called out, ‘Ndiyindoda!’” [I am a man!].

“A boy may cry; a man conceals his pain”, he concludes. “To enter manhood, a piece of one’s own body has to be cut and buried in the earth in the middle of the night. The newly circumcised man has to paint his naked and shaved body from head to foot in white ochre. He must inhabit the appearance of a ghost.” (Long Walk to Freedom, pg. 27)

Mandela’s closest encounter with the prospect of his own death and his own ghost occurred during the Rivonia Trail in 1964. The public requirement to appear strong and brave as torchbearers of what is just and true was quite different from being in his cell alone and trying to confront the fact that he was likely “to not live”. He wrote: “I must however, confess that for my own part the threat of death evoked no desire in me to play the role of martyr. I was ready to do so if I had to. But the anxiety to live always lingered.”

One of the greatest internationalists of all time

Mandela’s awareness and consciousness grew as his education expanded. Growing up in Mvezo and Qunu he started out a Thembu loyalist; when he moved to Healdtown he became an African nationalist and when he moved to Johannesburg and became a lawyer and politician, he transformed into an internationalist. This remained with him throughout his time in prison and when he emerged, he evolved into one of the greatest internationalists of all time.

A twilight world

For years before his final arrest for treason and sentencing, Mandela lived in a twilight world, tipping this way and that between the worlds of the living and the dead, between day and night, the visible and the invisible, presence and absence.

It offers a parallel with the last years of his life when age and time repeatedly snatched and spared him. It was extremely difficult for the nation to face that Mandela had to leave us but it was inevitable, and, just as he had to leave his wife and family to join the liberation struggle with stoic inevitability, so too we had to release this remarkable man, while keeping his spirit alive in our hearts.

And, while we contemplate the gigantic contribution he has made to South Africa and the world, now and into the future, we need to remember that, like you and me, he was a human being with all the anxieties, attachments, joys, sorrows, fragilities and contradictions that none of us can avoid. Nowhere is this more poignantly expressed than in a letter to Winnie he once wrote: “Sometimes I feel like one who is on the sidelines…who has missed life itself.” It is a feeling with which many of us can identify in our own great and small ways, and it is comforting to know that a man like Madiba felt it too.